With Amici Like These . . .

by Michael C. Dorf

On Thursday of last week, the Supreme Court issued official guidance regarding the filing of amicus briefs. Most of it simply collects what's already in Supreme Court Rule 37, but even so it's useful. For a summary of the guidance (which is itself pretty short), here's a helpful article on Bloomberg. I'll offer some critical thoughts on a couple of points: (1) party consent; and (2) colors.

Under Rule 37 and as reiterated in the guidance, as a prerequisite to filing an amicus brief, the filer must either receive written consent from all parties or seek leave of the Court to file. The guidance document notes that many parties give blanket consent to the filing of amicus briefs. Sometimes parties will withhold blanket consent but agree to cross-approve each other's amici. Under such an arrangement, an amicus brief in support of petitioner that garners consent from petitioner will then receive automatic consent from respondent, and vice-versa. When the parties do not all consent to the filing of an amicus brief, the request for leave from the Court can be in the brief itself, typically explaining why the brief adds a valuable perspective.

This whole enterprise is misbegotten. The Court should simply abolish the requirement of consent with the backstop of leave and allow anyone and everyone who wants to file an amicus brief to do so. The fact that many parties give blanket consent shows that the world will not end if parties no longer play a gatekeeping role. And it's a waste of the Court's time to have to decide whether an amicus brief should be allowed. It's easier just to start reading and put down a brief that proves unhelpful.

Moreover, an amicus brief might be most useful in just those cases in which one or more parties don't consent to it, because in such circumstances there's a decent chance that the amicus brief presents information or arguments tending to show how various potential rulings could have third-party effects. Requiring consent of the parties seems rooted in the fiction that the Supreme Court sits to resolve disputes between parties. That's a formal limitation on its jurisdiction per the case-or-controversy requirement, but given the discretionary nature of Supreme Court review and its use in cases that present important questions, the Court is not a court of error.

Meanwhile, the Court's rules and their application are overall a bit picky. I can illustrate with my own run-in with the rules governing the color of a brief's cover. Rule 33 sets out the color requirements for the covers of briefs. A cert petition gets a white cover, an opp cert is orange, petitioner's merits brief is light blue, respondent's is red, etc. Crucially for our purposes: an amicus brief in support of the petitioner is light green, while an amicus brief in support of the respondent is dark green.

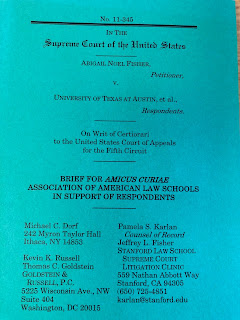

But what is dark green? Here's an amicus brief in which I had a hand in support of respondents:

That looks suspiciously like light green, which I think is mostly an artifact of the lighting in my office and the limits of my camera phone, but even in real life the two brief covers are somewhat different colors. Moreover, we can't attribute the lighter color of the second one above to fading, because it's a brief for a case being argued this Term. The good news is that it must have counted as sufficiently dark green for the Court to accept it.

Wait, what? You're thinking the Court doesn't reject briefs for being the wrong shade of green. Think again. Here's an amicus brief on behalf of respondent that got me into trouble in the late 1990s:

After the brief was filed, the clerk's office contacted my co-counsel and me to tell us that it was rejected because one of the justices complained that it wasn't dark green. In my defense, I actually didn't know what color the cover was at the time. I'm not color-blind, but I didn't see the cover before it was filed. Co-counsel and I were donating our time and a law firm was donating its support services, which meant printing and binding the brief. We emailed the firm the final version as a Word doc in black and white, the firm printed it, including putting the cover page on the "dark green" stock, bound it, and delivered the requisite number of copies to the Court and the parties. (These were the days before the electronic filing requirement.) Because co-counsel and I hadn't seen the filed version of the brief, when the clerk told us the cover wasn't dark green, we assumed it was some very different color. We contacted the firm immediately; it produced a more conventional dark green cover; and that day we filed the substitute copies, along with a very short motion to allow the filing nunc pro tunc, in light of the fact that the version with the improper color cover had been filed within the deadline. The Court accepted the re-filed version and Justice Souter even cited it in his concurrence in the judgment in the case (which the side we were supporting lost unanimously).

A few days later, I received in the mail the original version shown above. I admit that it is a somewhat creative take on dark green, more of a greenish gray, I suppose, but come on! Really? What possible purpose was served by requiring the reprinting and re-filing of a brief just so its cover would be more clearly dark green? Is there some serious risk that if the justices don't police the color of brief covers anarchy will be unleashed at One First Street, NE? Will parties and amici start filing briefs with hot pink covers to draw attention? Rainbow-covered briefs? Bedazzled briefs? And if any of that were to occur, wouldn't that be, I don't know . . . kind of awesome?

By contrast with my proposal to abolish the consent requirement for amicus briefs, I don't propose abolishing the requirements of different colors for different briefs. The rule is relatively easy to comply with (especially if one uses the services of the very small number of companies that specialize in printing Supreme Court briefs) and serves a reasonable purpose: it enables the staff of the justices to file briefs in an orderly fashion without examining them closely. But I do think that, as my experience illustrates, there's no point in expending any resources in strictly enforcing the color limits.

On Thursday of last week, the Supreme Court issued official guidance regarding the filing of amicus briefs. Most of it simply collects what's already in Supreme Court Rule 37, but even so it's useful. For a summary of the guidance (which is itself pretty short), here's a helpful article on Bloomberg. I'll offer some critical thoughts on a couple of points: (1) party consent; and (2) colors.

Under Rule 37 and as reiterated in the guidance, as a prerequisite to filing an amicus brief, the filer must either receive written consent from all parties or seek leave of the Court to file. The guidance document notes that many parties give blanket consent to the filing of amicus briefs. Sometimes parties will withhold blanket consent but agree to cross-approve each other's amici. Under such an arrangement, an amicus brief in support of petitioner that garners consent from petitioner will then receive automatic consent from respondent, and vice-versa. When the parties do not all consent to the filing of an amicus brief, the request for leave from the Court can be in the brief itself, typically explaining why the brief adds a valuable perspective.

This whole enterprise is misbegotten. The Court should simply abolish the requirement of consent with the backstop of leave and allow anyone and everyone who wants to file an amicus brief to do so. The fact that many parties give blanket consent shows that the world will not end if parties no longer play a gatekeeping role. And it's a waste of the Court's time to have to decide whether an amicus brief should be allowed. It's easier just to start reading and put down a brief that proves unhelpful.

Moreover, an amicus brief might be most useful in just those cases in which one or more parties don't consent to it, because in such circumstances there's a decent chance that the amicus brief presents information or arguments tending to show how various potential rulings could have third-party effects. Requiring consent of the parties seems rooted in the fiction that the Supreme Court sits to resolve disputes between parties. That's a formal limitation on its jurisdiction per the case-or-controversy requirement, but given the discretionary nature of Supreme Court review and its use in cases that present important questions, the Court is not a court of error.

Meanwhile, the Court's rules and their application are overall a bit picky. I can illustrate with my own run-in with the rules governing the color of a brief's cover. Rule 33 sets out the color requirements for the covers of briefs. A cert petition gets a white cover, an opp cert is orange, petitioner's merits brief is light blue, respondent's is red, etc. Crucially for our purposes: an amicus brief in support of the petitioner is light green, while an amicus brief in support of the respondent is dark green.

But what is dark green? Here's an amicus brief in which I had a hand in support of respondents:

That looks dark green, but here's another one I recently had a hand in, also for respondents:

That looks suspiciously like light green, which I think is mostly an artifact of the lighting in my office and the limits of my camera phone, but even in real life the two brief covers are somewhat different colors. Moreover, we can't attribute the lighter color of the second one above to fading, because it's a brief for a case being argued this Term. The good news is that it must have counted as sufficiently dark green for the Court to accept it.

Wait, what? You're thinking the Court doesn't reject briefs for being the wrong shade of green. Think again. Here's an amicus brief on behalf of respondent that got me into trouble in the late 1990s:

After the brief was filed, the clerk's office contacted my co-counsel and me to tell us that it was rejected because one of the justices complained that it wasn't dark green. In my defense, I actually didn't know what color the cover was at the time. I'm not color-blind, but I didn't see the cover before it was filed. Co-counsel and I were donating our time and a law firm was donating its support services, which meant printing and binding the brief. We emailed the firm the final version as a Word doc in black and white, the firm printed it, including putting the cover page on the "dark green" stock, bound it, and delivered the requisite number of copies to the Court and the parties. (These were the days before the electronic filing requirement.) Because co-counsel and I hadn't seen the filed version of the brief, when the clerk told us the cover wasn't dark green, we assumed it was some very different color. We contacted the firm immediately; it produced a more conventional dark green cover; and that day we filed the substitute copies, along with a very short motion to allow the filing nunc pro tunc, in light of the fact that the version with the improper color cover had been filed within the deadline. The Court accepted the re-filed version and Justice Souter even cited it in his concurrence in the judgment in the case (which the side we were supporting lost unanimously).

A few days later, I received in the mail the original version shown above. I admit that it is a somewhat creative take on dark green, more of a greenish gray, I suppose, but come on! Really? What possible purpose was served by requiring the reprinting and re-filing of a brief just so its cover would be more clearly dark green? Is there some serious risk that if the justices don't police the color of brief covers anarchy will be unleashed at One First Street, NE? Will parties and amici start filing briefs with hot pink covers to draw attention? Rainbow-covered briefs? Bedazzled briefs? And if any of that were to occur, wouldn't that be, I don't know . . . kind of awesome?

By contrast with my proposal to abolish the consent requirement for amicus briefs, I don't propose abolishing the requirements of different colors for different briefs. The rule is relatively easy to comply with (especially if one uses the services of the very small number of companies that specialize in printing Supreme Court briefs) and serves a reasonable purpose: it enables the staff of the justices to file briefs in an orderly fashion without examining them closely. But I do think that, as my experience illustrates, there's no point in expending any resources in strictly enforcing the color limits.