(When) Will SCOTUS Hold that the Establishment Clause Violates the Free Exercise Clause?

by Michael C. Dorf

Because of its low population density, Maine cannot afford to provide local public schools for all children in the state. Instead, parents of students in various rural districts throughout the state can receive tuition assistance (what I'll call vouchers) to pay for (some, most, or all of, depending on tuition) their children's education at an accredited private school, so long as the education the school provides is "nonsectarian," i.e., not religious. Until twenty years ago--when the Supreme Court decided Zelman v. Simmons-Harris--it would have been very plausible to argue that Maine's exclusion of religious schools from its voucher program was constitutionally required by the First Amendment's Establishment Clause. Zelman rejected that view and upheld what the Court deemed a neutrally structured system of vouchers that were redeemable at religious along with secular schools. Yesterday's 6-3 ruling in Carson v. Makin held that the state's failure to fund religious schools through its vouchers program is itself an unconstitutional violation of the parents' right to free exercise.

Thus, in the space of two decades, education vouchers redeemable at private religious schools went from (1) arguably unconstitutional as a violation of a core no-aid-to-religion principle to (2) constitutionally permissible if vouchers are also redeemable at secular private schools to (3) constitutionally mandated if vouchers are also redeemable at secular private schools. Or as Justice Sotomayor put the point in her dissent yesterday, "the Court leads us to a place where separation of church and state becomes a constitutional violation."

As both Justice Sotomayor's dissent and a separate dissent by Justice Breyer (joined in whole by Justice Kagan and in substantial part by Justice Sotomayor) made clear, Carson appears to mark the effective end of a concept known as "play in the joints," according to which federal, state, and local government officials have some freedom to choose policies implicating religion that violate neither the Free Exercise Clause nor the Establishment Clause. Although the majority opinion of Chief Justice Roberts cites and does not purport to overrule leading play-in-the-joints cases like Locke v. Davey, he essentially confines those cases to their facts.

The dissenters (and I) lament the apparent demise of play-in-the-joints because that demise erodes democracy and federalism by judicializing all the difficult line-drawing issues in this area. But the fate of play-in-the-joints is ultimately less important than the larger process seemingly at work in Carson and other recent cases. After all, we can envision a regime that retains some space for play-in-the-joints but nearly eviscerates the Establishment Clause.

For example, imagine that the Court were to say that the Free Exercise Clause requires that all public government functions begin with an official prayer but that it merely permits the prayer to be "in the name of Jesus Christ." (If you're wondering, we're almost but not quite there yet.) There would be play in the joints in the sense that elected officials would have some freedom of movement, some space between the Free Exercise and Establishment Clauses, but the space taken up by the Free Exercise Clause would be enormous and that taken up by the Establishment Clause tiny. More fundamental than the size of the region between Free Exercise and Establishment is the scope of each clause.

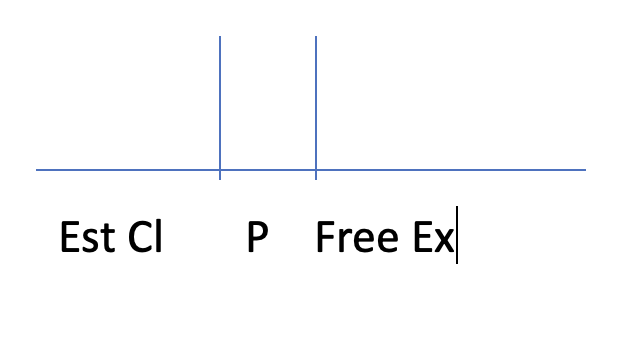

I can illustrate that proposition graphically. Here is how the Establishment Clause and Free Exercise Clause worked when each was substantial and there was play-in-the-joints (with the region called P for play-in-the-joints ungoverned by either religion clause and thus allowing elected officials freedom):

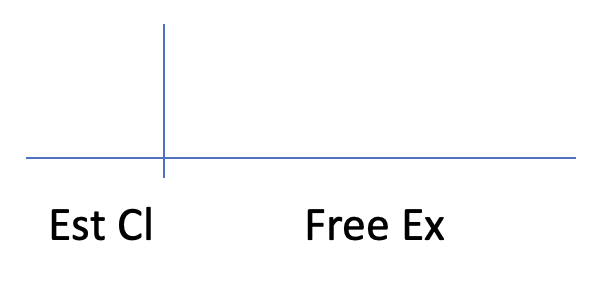

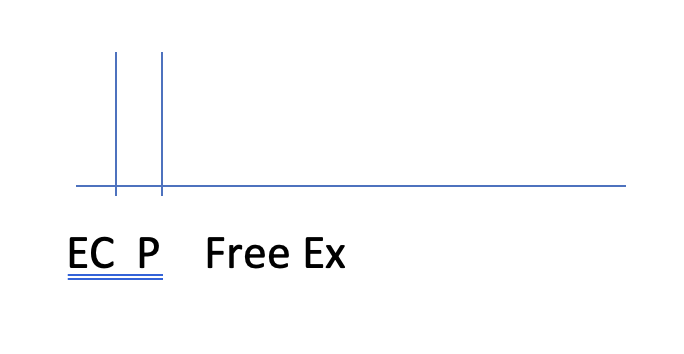

And here is how the clauses look if Free Exercise swallows up some of what used to be Establishment, leaving no room for play-in-the-joints:Bad as the foregoing is on judicial usurpation grounds, we could end up with something even worse, a scheme that retains a play-in-the-joints region but shrinks the Establishment Clause area down to almost nothing:Just how much of the Establishment Clause the Roberts Court's free exercise jurisprudence ends up swallowing remains to be seen. The majority opinion in Carson says that if Maine wants to provide only secular public schools it can still do so, but that while the program at issue in the case may be designed in some sense to substitute for public schools, the private schools at which Maine parents can redeem vouchers are sufficiently different from public schools that the overall scheme should be regarded as a voucher program. As Justice Breyer notes in dissent, even so, the notion that states must include private religious schools in a voucher program if they include private secular schools is a step beyond the two recent cases on which the majority relies: Trinity Lutheran v. Comer and Espinoza v. Montana Dep't of Revenue. But as Justice Sotomayor's dissent acknowledges, it's hardly an unexpected step.