Why Is It So Difficult for Pundits to Understand Gerrymandering?

by Neil H. Buchanan

At

long last, the mainstream press and some of the pundits who are

accepted in polite society are taking more and more seriously the idea

that the US might soon cease to be a functioning constitutional

democracy. I continue

to believe that it is already too late to prevent the worst from

happening, but I also remain willing to reassess my predictions as new

evidence comes in.

Although

Democrats have recently been feeling better about their chances in the

midterms, there are still plenty of reasons to think that it will all go

very badly for them (and the country) on November 8. As but one among

many examples, despite being one of the weakest candidates in the

history of the country, Georgia's Republican candidate for the Senate is

actually leading in the polls. No matter how extreme or crazy (or

blatantly dishonest)

the Republican nominees are for key gubernatorial and US Senate races,

there is no evidence of any dams breaking as people say: "at long last, this is too

much."

My

purpose here, however, is not to predict electoral outcomes. That is

not my skill set, and frankly, I would seriously have to reconsider my

life choices if that is what I did for a living. Instead, I am

interested in the apparently unbreakable bad habits that cause people to

continue to misunderstand even the most basic threats to our political

system.

Until

recently, the Democrats had mostly been pretending that there was

nothing seriously wrong that some good fundraising and inoffensive

candidates could not solve. They now seem to have shaken themselves out

of

that slumber, and it has surprised everyone. Indeed, the Republicans

had no idea what to do when

President Biden actually called out their authoritarianism, so they

resorted to making over-the-top remarks about the lighting at the site of Biden's speech. In some ways, this is promising.

A very good example of this can be found in a recent long-form article by David Leonhardt in The New York Times: "'A Crisis Coming': The Twin Threats to American Democracy." I give The Times

a lot of credit for devoting resources to its new "Democracy

Challenged" series, of which Leonhardt's piece is the latest entry. He

clearly means well, and he covers plenty of interesting and important

ground. Even so, let me note two examples of bad old habits that show

up in the piece, reinforcing my worry that the people who need to stand

up and resist will lose their nerve -- or might not even know what needs

to be done.

Both

of the examples that I will focus on here have to do with

gerrymandering -- and again, I emphasize that there is a lot to like in

Leonhardt's piece -- but they are not the only worrisome lapses. I am

focusing on them because they are especially clear examples of the kind

of sleepwalking non-thinking that too often passes for political

analysis.

First,

there is the almost awesome ability to take even the most one-sided

problem and present it with classic bothsidesism: "In Illinois, for

example, the Democrats who control the state government

have packed Republican voters into a small number of House districts,

allowing most other districts to lean Democratic. In Wisconsin,

Republicans have done the opposite." See, both parties are bad!

But

hey, maybe that is just a framing device. After all, the very next

paragraph concedes that "Republicans have been more forceful than

Democrats about gerrymandering," even linking to a report that some

illegally gerrymandered maps are being used in 2022 because the Supreme

Court's reactionary majority is allowing it. Nonetheless, we are told

that "the current House map slightly favors Republicans, likely by a few

seats." But this is after

Republicans added at least eight safe seats nationwide, while Democrats

were stopped from responding in kind in several states. In light of

that, if the overall Republican advantage is only a few seats, that

merely means that the Democrats would be outright favored in a

non-gerrymandered world, not fighting from a disadvantage.

More to the point, the idea that "both sides do it" is simply ridiculous in this context. Of course

Democrats are trying to do what they can to counter Republican

gerrymanders. They are a political party, and they know hardball when

they see it. But if both parties were given the chance to vote for a

system with no gerrymandering (with enforceable guarantees that both

parties will be prevented from using redistricting to achieve an unfair

advantage), we all know that the Republicans would say no and that

Democrats would say yes. (Indeed, the Republicans on the Supreme Court

have done exactly that.) That is not necessarily because Democrats are

inherently virtuous, but the simple fact is that their gerrymandering is

defensive, not offensive.

In

mainstream pundit-land, however, only people who are willing to

unilaterally disarm are viewed as sufficiently pure of heart.

Apparently, Democrats would have to commit themselves to the practice of

Gandhi's Satyagraha before they would be permitted to complain about gerrymandering.

Second,

Leonhardt then defaults to another myth about gerrymandering, which is

the idea that the Democrats' disadvantage in the House is partly

non-Republican voters' fault, because they have moved into cities and

thus supposedly made it impossible not to gerrymander them into

too-safe Democratic districts. He even has a citation to a political

scientist who has made that argument.

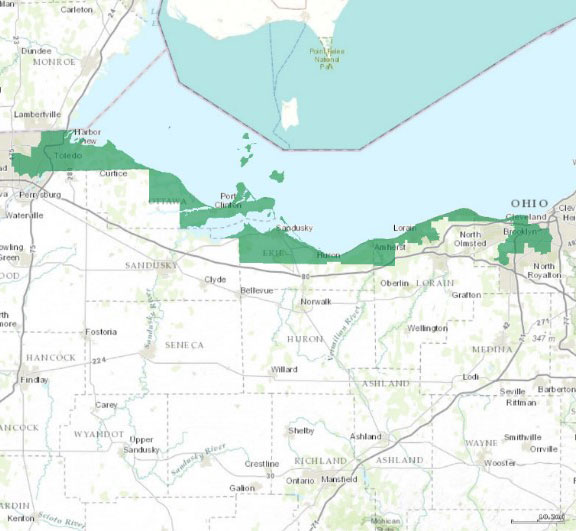

But as I described in a column here on Dorf on Law

five years ago, that is nonsense on stilts. It is simply false to say

that an all-Democratic area makes it impossible to draw districts that

are competitive and have partisan balance. District lines are drawn

through cities all the time, joining urban, suburban, and rural areas in

all kinds of ways. When I was growing up in a suburb of Toledo, Ohio,

the 9th congressional district was essentially the city of Toledo and a

few of the surrounding suburbs. I was still registered there when

Congresswoman Marcy Kaptur won her first term in the House. Here is her

current district map,

running from Toledo along empty areas of the Lake Erie coast,

connecting to Sandusky (and Cedar Point) and then all the way to the

Cleveland suburbs.

Thanks

to Ohio's gerrymandered Republican state legislative majorities, Kaptur

has been re-redistricted into an area that still includes Toledo but

that now runs west to the Indiana border, an area that Donald Trump won

in 2020. Interested readers can see that map here,

but the previous map above makes my point clearly. Does anything about

that map suggest that there are limits as to the shape of congressional

districts -- limits that make it impossible for a map-maker acting in

good faith to undo non-Republican voters' supposed "geographic

sorting"? Even contiguity is not completely honored, with the rather

large Sandusky Bay breaking up the land mass.

And

Ohio's 9th is hardly an outlier. Even before the Roberts Court decided

to take gerrymandering even less seriously, the only limits on

gerrymandering were related to racially discriminatory district maps.

Republicans openly admitted that they were gerrymandering, but they said

that it was acceptable to do so because they were merely harming

Democrats qua Democrats, not targeting minorities deliberately or

specifically. Indeed, they defended themselves all the way up to the

Court's disastrous 2018 punt

on gerrymandering by saying, in essence, that they should be able to

get away with whatever they want, because deciding what counts as

excessive gerrymandering is just too hard.

Even

so, Leonhardt writes: "The increasing concentration of Democratic

voters into large metro areas

means that even a neutral system would have a hard time distributing

these tightly packed Democratic voters across districts in a way that

would allow the party to win more elections." Again, that is not only

wrong but trivially and obviously illogical. And Republicans know it.

So here we have an essay in The New York Times

purporting to describe the dangers facing our democracy, yet somehow

managing to make one of the most important Republican strategies

distorting our system seem innocuous and even somehow natural.

Fifty-two percent of Alabamans identify

as Republican or "lean Republican," but six of that state's seven

congressional districts elect Republicans. Is that because it is

impossible to distribute Democrats in Mobile and Birmingham into

competitive districts, because Democrats self-sorted into huge and

impenetrable cities? Get serious.

And Florida's Republicans were not able to add turn

3 competitive congressional districts (plus one new district) into safe

Republican seats in a single cycle because too many Democrats moved to

downtown Tampa and Miami. We could also flip the script: Does anyone

think that Republicans would not be able to "crack" bright-blue New York

City in a way that would kill off a few Democratic seats?

Again,

Leonhardt's piece has its virtues, chief among them his newfound

willingness to discuss openly the idea that the Republican Party is no

longer committed to democracy. Even so, his blithe acceptance of

assumptions that at best have only ever been partially true and that now

have been completely overtaken by events, combined with good

old-fashioned bothsidesism, is emblematic not merely of one journalist's

laziness but of the difficulty that too many people have in accepting

reality. Even when warning that Republicans are an existential threat

to our constitutional system, the instinct is to cower and say, "but not

too much of a threat."

This

should not be acceptable. When the history of American democracy is

written, we will find that a key element in its demise was the timidity

of people who ought to have known better and who should have tried

harder to move beyond conventional wisdom.